In her highly controversial 1962 bestseller Silent Spring, author Rachel Carson argued that the uncontrolled and widespread use of such pesticides as DDT was killing a wide variety of birds that were facing the possibility of extinction if something wasn’t done to address the problem.

Fifty years later, a young graduate student at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research is discovering  that many of those same chemicals are becoming highly concentrated in young fish species that fail to shed them at the same rate they lose fat shortly after hatching.

that many of those same chemicals are becoming highly concentrated in young fish species that fail to shed them at the same rate they lose fat shortly after hatching.

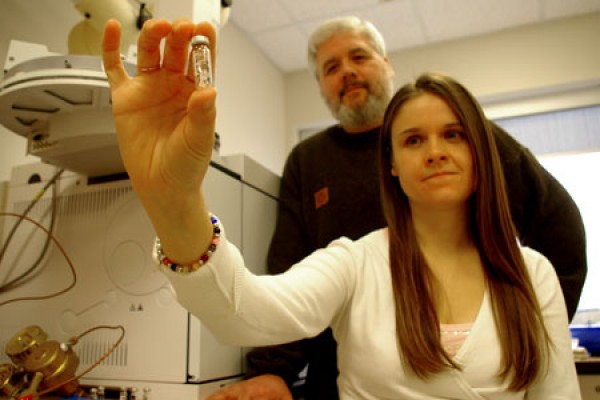

It’s a process PhD candidate Jennifer Daley has coined “bioamplification” and it’s documented in a paper she authored that was recently accepted for publication in the academic journal Environmental Science and Technology.

“Basically, it occurs when organisms lose body weight and fat faster than they can lose contaminants, resulting in a concentration effect of chemicals in their tissues,” explained Daley, whose work is supported by a Canada Graduate scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Under the tutelage of GLIER professor Ken Drouillard and Biological Sciences professor Trevor Pitcher, Daley travelled last year to the Credit River, a tributary that runs off Lake Ontario near Mississauga. There, they captured a female salmon, brought her eggs back to Windsor and inseminated them in their labs. The fertilized eggs were then placed in water from the Detroit River to mimic the normal seasonal temperature cycle, and allowed to hatch.

The eggs and newly hatched fry were weighed and tested for contaminant levels nine times over a 168-day period. The researchers expected the fish would shed those contaminants as their fat levels decreased, but were shocked to find that even after they lost their yolk sacs – which remain attached after autumn hatching and supply them with energy during the winter under-ice period – the juvenile fish concentrated their PCB body burdens by an astounding 500 per cent compared to concentrations that were measured in the fresh laid eggs.

Dr. Drouillard said his student’s work builds on existing scientific literature on bioaccumulation, which is a progressive increase in the amount of a substance in an organism and occurs because the rate of intake exceeds its ability to remove that substance from its body. He said it was Rachel Carson’s work – which led to a new branch of science called ecotoxicology – that recognized certain chemicals undergo biomagnification, a special bioaccumulation process where they reach higher concentrations in the bodies of animals at the top of the food chain.

“(Bioamplification) has been recognised in the past, but it was never formally adopted in the bioaccumulation modelling literature,” he said. “Jen is the first person to define and fully investigate this new bioaccumulation .jpg) process.”

process.”

He also suggested it may be of particular interest to those working in the aquaculture sector, as well as the many people involved in efforts to restock lakes with a variety of fish species, especially considering that bioamplification occurs during a critical period of the fish’s life cycle and may determine its likelihood for survival.

Daley, who hopes to defend her PhD thesis later this year, will appear at 4:30 p.m. today on Research Matters, a weekly talk show that focuses on the work of University of Windsor researchers and airs every Thursday on CJAM 99.1 FM.