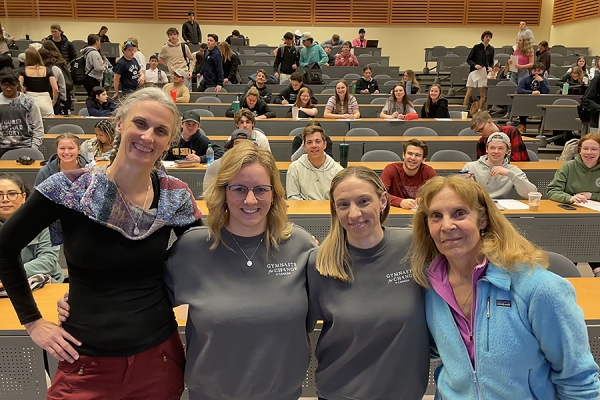

Kinesiology professor Krista Loughead welcomed Melanie Hunt, Abby Spadafora, and Victoria Paraschak to her “Ethics in Sport and Physical Activity” course to address abuse in Canadian sport.

Kinesiology professor Krista Loughead welcomed Melanie Hunt, Abby Spadafora, and Victoria Paraschak to her “Ethics in Sport and Physical Activity” course to address abuse in Canadian sport.

When former Canadian national gymnast Abby Spadafora attends her children’s sporting events, she watches coaches and parents as much as the action.

Spadafora was verbally, psychologically, physically, and sexually abused by coaches during her years as a club gymnast. Adult witnesses to the abuse — coaches and parents — kept mum.

Spadafora won’t ever make that same mistake.

Spadafora and former national team gymnast Melanie Hunt were in the Faculty of Human Kinetics last week to address kinesiology professor Krista Loughead’s “Ethics in Sport and Physical Activity” class. The previous night, they were among a panel of speakers at an event to raise awareness about the toxic culture in Canadian sport.

Hunt and Spadafora shared their experiences and spoke about the organization they founded: Gymnasts for Change Canada. The group supports abuse survivors from myriad sports including swimming, taekwondo, and hockey.

“From our experience, there doesn’t seem to be ethics in sport,” Hunt told students.

She was abused by the same coaches as Spadafora. Their male coach was eventually banned from coaching gymnastics, but not other sports. Hunt and Spadafora’s attempts to bring him to justice victimized them and the other gymnasts who came forward all over again.

There is no governing body for coaches in Canada, Hunt explained. And while individual sports organizations may have policies to reduce instances of abuse, those policies are open to interpretation, Spadafora added.

Their club had a reporting mechanism, but it was broken. Their abusive coach was also the club’s executive director, so he reported to himself.

Spadafora said children like herself and their parents were “brainwashed” into believing coaches were infallible. Parents weren’t allowed to watch practices where the abuse would take place. The children kept silent because the abuse would get worse if their parents said a critical word.

Spadafora recounted how her coach threw her around the gym like a rag doll. Once, after criticizing her hand positioning on the uneven bars, the coach placed her in a handstand position on the lower bar then sent her crashing into the ground headfirst. She remembers laying dazed on the ground as her coach stood over her threatening to do it again.

She never told her parents. Neither did the other children and adults who witnessed it.

Believing her coach had her best interests at heart and was her ticket to the Olympics, Spadafora’s parents allowed her to move in with him and his wife in another city.

That’s when the sexual abuse began.

Spadafora never told a soul until she reluctantly opened up to police after another victim came forward years later.

Hunt later lived with the same couple, enduring the same abuse. She recalled injuring both knees during a competition and being unable to walk. Her coach carried her to his bed that night.

Beyond the physical and sexual abuse, the win-at-all-costs culture of sport damaged them, the women said.

They were weighed twice a day and placed on low-carb diets by age 12. Hunt recalls her male coach pinching her buttocks and calling her fat and ugly in front of other children and coaches. When she lived with the coach and his wife, she recalls her diet being so strict that when she visited her parents on the weekends, she would gorge herself. After gaining five pounds one weekend, the visits home ended.

Both women attended universities in the United States. It was there, removed from the environment in which they’d been immersed, that they came to recognize what they’d endured as abuse.

“You leave the sport and you’re broken,” Hunt said.

Hunt and Spadafora’s classroom visit included an appearance by professor emerita Victoria Paraschak. Dr. Paraschak started a petition last year calling on the federal government to launch a judicial inquiry into abuse in Canadian sport.