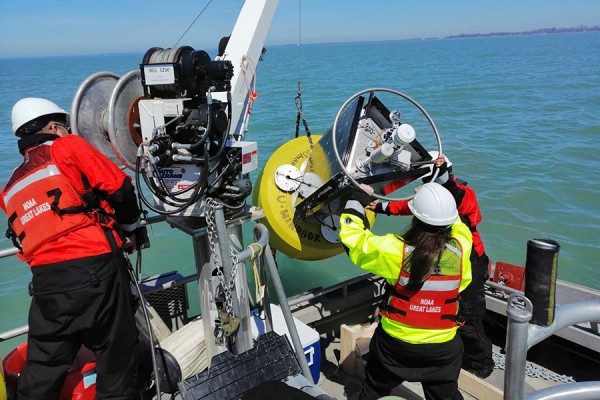

Scientists deploy real-time monitoring equipment in Lake Erie to establish drivers of algal blooms. From left: Kent Baker, Jill Crossman, Danna Palladino. Photo by Fabio Massimo Pasquazzi.

Scientists deploy real-time monitoring equipment in Lake Erie to establish drivers of algal blooms. From left: Kent Baker, Jill Crossman, Danna Palladino. Photo by Fabio Massimo Pasquazzi.

A resurgence of harmful algal blooms in the Lake Erie watershed has raised concerns over toxicity and low dissolved oxygen levels and their negative impacts on fish and drinking water.

UWindsor researcher Jill Crossman, assistant professor of quantitative hydrology at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, has established four buoys in Lake Erie to quantify nutrients levels in real time. These buoys report nutrient levels by cellular network to computers and cellphones, a first for the Great Lakes.

The project is a central component of “ErieWatch,” Dr. Crossman’s new research program aimed at understanding drivers of algal blooms in Lake Erie and its tributaries. The instruments and technical support were provided by the University of Windsor’s recently funded $17 million Realtime Aquatic Ecosystem Observation Network (RAEON), and the UWindsor Office of Research and Innovation.

This work also received support from US partners, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, the Co-operative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan, engineering and science firm LimnoTech, and Systea, the manufacturers of the real-time nutrient sensors.

RAEON science director Aaron Fisk says this is the network’s first significant deployment of equipment.

“Dr. Crossman’s buoys are equipped with state-of-the-art real-time phosphorous analyzers providing novel resolution necessary for understanding and ultimately controlling increasing harmful algal blooms in the Great Lakes basin,” says Dr. Fisk. “This work would not have been possible without RAEON instruments and technical support.

“We are putting federal and provincial funding to work to solve real-world environmental problems.”

The buoys are currently based at Sturgeon Creek in Leamington and in the shoreline of Pigeon Bay in Lake Erie and will remain there until about early November. Each year they will be moved to a different tributary to collect and build the most comprehensive dataset of nutrients in the Great Lakes.

Algal blooms were a concern in the Lake Erie watershed back in the 1970s, when reduction of phosphorous loads successfully reduced their occurrence. There has since been a resurgence in algal blooms in Lake Erie — and now, many other areas of the Great Lakes. These blooms have led to drinking water advisories in communities across Lake Erie.

“These blooms have a higher dominance of toxic algae and are a concern for wildlife and human health,” says Crossman. “While phosphorous is a key concern, the buoys will also monitor for additional factors that may be influencing the algal blooms, including light, temperature, surface current, and other nutrients such as nitrogen.”

These buoys and instruments, along with additional RAEON equipment to be deployed in the coming years, are a game changer in protecting the Great Lakes.

“The goal is to determine what influences these algal blooms,” says Crossman. “Knowing this will help us develop effective management strategies.”

—Darko Milenkovic