Authors

Christine K. Becher, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Peregrine_Notes@yahoo.comJohn Hartig, Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, jhhartig@uwindsor.ca

Background

Peregrine falcons, known for their swift flight, have never been very abundant anywhere in the world due to very specific nest site requirements and their position at the top of the food web. A 1940 survey of eyries (nesting sites) estimated that the eastern U.S. population consisted of only 350 pairs. The upper Midwest population was estimated to be 109 pairs, before a dramatic decline in the 1950s. Historically, there were 13 known eyries in Michigan, all located in the cliffs of the Upper Peninsula (Huron Mountains, Pictured Rocks, Mackinac Island), except for some found in steep sand dunes on the Fox Islands in northern Lake Michigan. The last documented successful nesting in Michigan, before restoration began, was in 1957 at Burnt Bluff, a cliff on the Garden Peninsula in Delta County (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2001).

During the 1950s, the world population of peregrines was decimated, mostly due to the use of pesticides like DDT (Tordoff and Redig, 1997). When DDE, the breakdown product of DDT, accumulates in the bodies of many birds, it causes them to lay very thin-shelled eggs which broke during incubation (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2001). Studies show the peregrine falcon retains the highest DDT residue of all vertebrates, causing reproductive problems (Apple et al. 2002). A repeat of the 1940 survey of historically known eyries, conducted in 1964, found no breeding pairs or even single adult peregrine east of the Mississippi River. As a result, the peregrine falcon was listed as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1970. The peregrine falcon was also included in the first list of endangered species promulgated under Michigan's Endangered Species Act in 1974 (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2001).

By the 1970s, DDT had been banned in both Europe and the U.S., partially due to data linking it to the decline of the peregrine falcon. In 1981, the Midwest Peregrine Falcon Restoration Team was created and charged with the task of developing a management plan to restore peregrine falcons as a nesting bird population in the upper Midwest.

A highly successful program for Midwest re-introductions into urban environments was started in 1982. Peregrine chicks of captive adults were raised in artificial structures and subsequently released into their new urban environment. These new homes, including buildings of all shapes and sizes, bridges, power plant stacks, all having success stories, so that in 2005, over 90 cities had peregrine falcons nesting efforts recorded in the Midwest. Peregrines feed exclusively on other birds which are abundant in urban areas, such as pigeons, mourning doves, starlings, flickers and woodcocks (Apple et al. 2002). It is also thought that as these “urban” raised peregrines expanded their territories, they would naturally seek out some of the natural, more traditional sites, such as cliffs in the upper peninsula of Michigan.

By 1991, over 3,000 captive breed peregrines had been released throughout the U.S., including 400 in the upper Midwest, 139 in Michigan (108 in the Upper Peninsula and 31 in Grand Rapids and Detroit) (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2001). As of 2005 more then 20 peregrines have been observed either nesting or attempting to nest in southeast Michigan (Figure 1). Birds released from Sudbury, Ontario and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania formed a pair that became the first to successfully nest in Michigan, at the Book Building in downtown Detroit in 1993 (Yerkey 2004).

Figure 1. Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) (Photo Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

The year 1999 will be recognized as a milestone year for the restoration of endangered species. On August 20th, the peregrine falcon "soared" off the list of federally endangered species. This triumph is significant, due to the fact that the eastern population of peregrine falcons had been completely eliminated by the mid-1960s. At the time restoration began, the population of peregrines in the U.S. was probably down to about 10% of its original size (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2001). Reintroducing captive bred falcons into the wild proved to be successful in restoring a population of wild reproduced peregrines. (Figure 2 and 3)

Figure 2. Hacking box with a peregrine falcon at The Fisher Building in downtown Detroit , 2006 (photo credit: Barb Baldinger).

Figure 3. Peregrine falcon young in a hacking box at The Fisher Building in downtown Detroit, 2006 (photo credit: Barb Baldinger).

Status and Trends

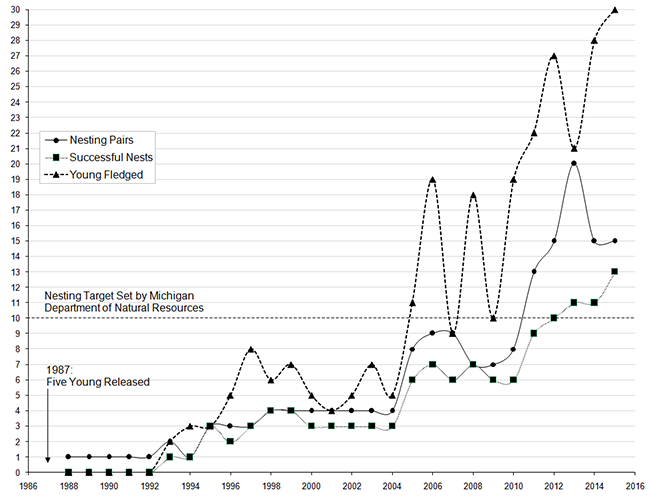

Michigan started the introduction program, with a goal of 10 successful nesting pairs by 2000, with the first release site in 1986 at a Grand Rapids location. In 1987, five peregrine falcon young were released in downtown Detroit. In 1988, one sub-adult pair was present when the five chicks were released; however this pair did not successfully nest. For the next four years various pairs continued to “visit” each year with no nesting success. Then, in 1993, two young peregrines were successfully raised for the first time documented in Detroit’s history, and the first in the Lower Peninsula in 37 years. The number of nesting sites in southeast Michigan, including the Ambassador Bridge, has increased from one in 1989-1992 to 13-20 in 2011-2016 (Figure 3). Further, the number of young produced in southeast Michigan increased from none in 1992 to 22-30 per year in 2011-2016 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Trends in nesting pairs, successful nests, and young fledged of peregrine falcons in southeast Michigan (including the Ambassador Bridge), 1987-2016. Data were provided by Michigan Department of Natural Resources and The Canadian Peregrine Foundation.

Southeast Michigan, especially along the Detroit River and its connecting waterways, is a significant part of the peregrines habitat in Michigan. The increase in the number of successful peregrine falcon nest sites in southeast Michigan over time demonstrates an expansion in range. In addition, peregrine falcons began nesting on the Canadian side of the Ambassador Bridge in 2008, with the first young fledged in 2010. In 2016, five young were fledged from this Ambassador Bridge location.

Management Next Steps

In 1999, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service delisted the peregrine falcon as a federally endangered species. However, it remains protected federally under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In Michigan, peregrines remain listed as an endangered species under state law.

The goal of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources' Natural Heritage Program (nongame wildlife) – to maintain a population of at least 10 nesting pairs of peregrine falcons in Michigan – has now been met.

The peregrine falcon is also identified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need by the Michigan Wildlife Conservation Strategy (Eagle et al. 2005). Management next steps include developing, protecting, and enhancing nesting and fledging habitat structures, including artificial nests, in the Detroit Metropolitan Area. This will involve close cooperation with building managers to minimize disturbance and allow for volunteers to assist in peregrine behavior observations. This volunteer effort will extend to raptor rehabilitators that will assist in restoration of sick and injured peregrines back into the wild. To accomplish this, a larger coordinated volunteer effort will be needed where collaboration with many partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Detroit Zoo, and others. Where possible, young peregrines will be banded as a part of an educational and outreach events.

Research/Monitoring Needs

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources’ Wildlife Division has provided funding to monitor falcon populations in the metropolitan Detroit area to gain a better understanding of this unique raptor. A priority should be placed on sustaining this long-term monitoring program with support from Michigan Department of Natural Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other conservation partners. In addition, a priority should be placed on building the capacity of this monitoring program using citizen science – where volunteers are recruited, trained, and equipped to sustain this valuable monitoring program.

There have been cases of mortality stressing the local population caused by bad weather, predators, such as the great horned owl, and incidental deaths. More research on the causes of mortality and improvements to decrease that mortality rate could be beneficial. Also, continued research of peregrine falcons throughout their current range could aid in a better understanding of nationwide environmental stressors and mortality. Additional research should be conducted on fledglings that are produced in metropolitan Detroit and leave the area to determine if they are reproducing successfully and where they nest.

References

- Apple, L.M., J.A. Craves, M.K. Smith, B. Weir and J.M. Zawiskie. 2002. Urban Wildlife. Explore our Natural World: A Biodiversity Atlas of the Lake Huron to Lake Eire Corridor. 125 pp.

- Eagle, A. C., E. M Hay-Chmielewski, K.T. Cleveland, A.L. Derosier, M.E. Herbert, and R.A. Rustem. 2005. Michigan’s Wildlife Action Plan. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Lansing, MI. 12 pp.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources. 2001. Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus).

- Tordoff, H.B. and P. Redig. 1997. 1997. Midwest peregrine falcon demontraphy, 1982-1995. J. Raptor Res. 31 (4) :339-346.

- Yerkey, J.M. 2004. S’East Mi Peregrines 1987-2004 (“an overview”). Unpublished report.

Links for more information

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources

http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,4570,7-153-10370_12145_12202-32592--,00.htm - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, American Peregrine Falcon:

https://www.fws.gov/species/american-peregrine-falcon-falco-peregrinus-anatum - University of Michigan Museum of Zoology:

http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Falco_peregrinus.html

Contact Information regarding Peregrine Falcon Reproduction in Southeast Michigan

Christine K. Becher

Southeast Michigan Peregrine Falcon Nesting CoordinatorMichigan Department of Natural Resources

Email: Peregrine_Notes@yahoo.com

John Hartig

Refuge ManagerDetroit River International Wildlife Refuge

E-mail: jhhartig@uwindsor.ca