Authors

Tammy Dobbie, Point Pelee National Park, tammy.dobbie@canada.caStephen Hecnar, Lakehead University, shecnar@lakeheadu.ca

Background

Point Pelee National Park is located in southwestern Ontario at the southernmost point of the Canadian mainland. It was established as a national park in 1918 to protect significant natural resources and ecological processes. The park consists of 420 hectares (1,039 acres) of Carolinian forest and 1070 hectares (2,644 acres) of freshwater marsh. It has been identified a “Wetland of International Importance” under the Ramsar Convention of UNESCO. Although it is one of Canada’s smallest national parks, it is well known for its biodiversity, with a unique and rare assemblage of plants and animals. The park is also world renowned for the viewing of migratory birds in the spring and Monarch butterflies in the fall.

The Common Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus) is a species of lizard in the family Scincidae (Figure 1). The species is endemic to eastern North America. The Carolinian population of the five-lined skink, currently listed as Endangered under the Species at Risk Act, is found primarily within the coastal Lake Erie Sand Spit Savannah (LESSS) habitat at Point Pelee. It is currently monitored mainly along the west beach of the park as an indicator of the health of the coastal ecosystem. The preferred habitat for this species has been improved over the past few decades through resource management programs to supplement woody debris and to restore LESSS habitat.

Figure 1. Common Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus)(credit: Point Pelee National Park).

Status and Trends

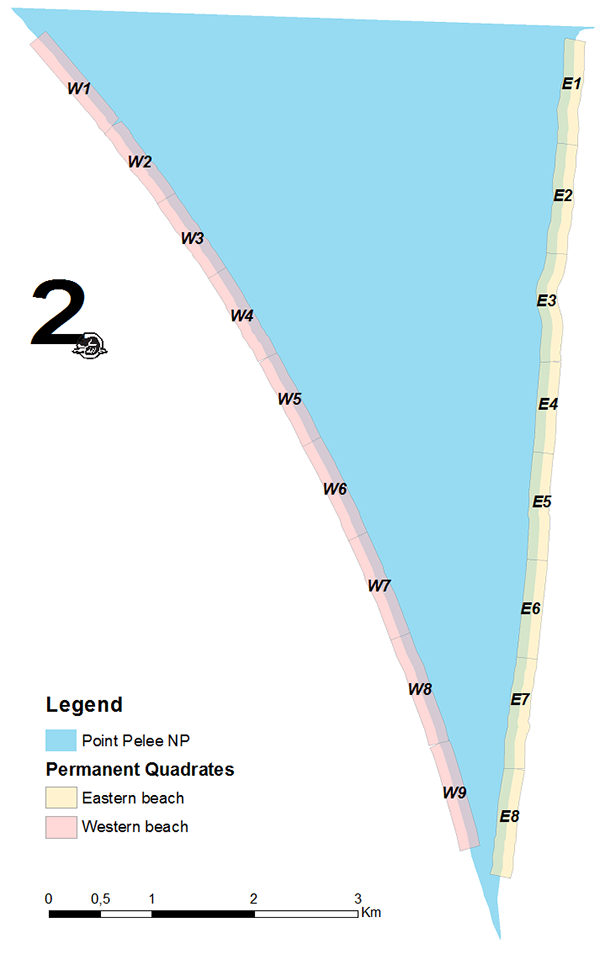

Monitoring of the Common Five-lined Skink was undertaken at Point Pelee National Park as part of long-term conservation efforts. Using the census data collected during 16 skink surveys from 1990-2012, 17 permanent quadrats, each 1 km in length, were established along the park beaches, on both the east and west sides (Figure 2). The quadrats were stratified, into high, medium and low, based on the density of skinks observed during these surveys. Three of the quadrats were removed from the sampling design due to time and access constraints, however, these quadrats contained such a low percentage of the population (1.6%) that their exclusion was not expected to significantly impact population estimates. Starting in 2015, all of the high-density quadrats are sampled every year, along with two medium and two low quadrats (n=10), so that all quadrats are sampled every two years.

Figure 2. Map of skink monitoring quadrats.

Quadrats were surveyed during the same time each year (late June-early July) during the peak of skink abundance and nesting activity. Quadrats were sampled by walking along the beach through the stabilized dune and cedar savannah habitats, checking under all woody debris and counting the total number of skinks and nests observed. Age class, sex, decay class of the woody debris, and number of eggs in each nest were also recorded.

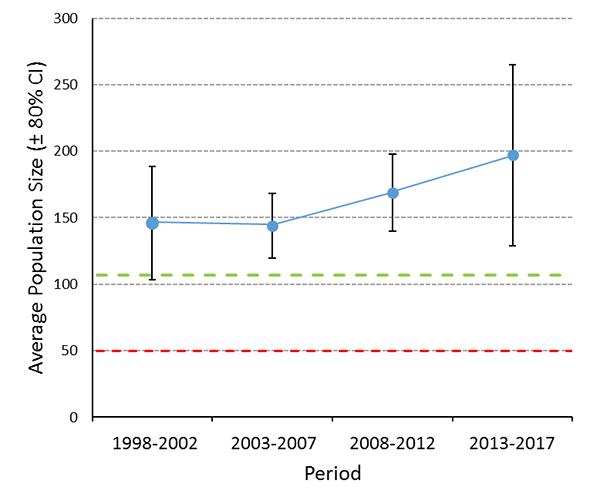

The condition of the skink population was determined by estimating the average abundance of skinks during the current monitoring period (2013-2017). The trend was assessed by comparing the 80% confidence intervals between the current and the previous period (2008-2012), where non-overlapping confidence intervals would indicate no significant change in abundance. See Parks Canada (2015) for more details of sampling design and statistical analysis.

The “Good-Fair” threshold for the skink population condition measure (107 skinks) was determined using one population standard deviation (±48.5) under the mean number of skinks observed in the 14 quadrats from 1990-2012 (155.3). The “Fair-Poor” threshold was determined using a population viability analysis based on the census data collected from 1990-2012. The risk of extinction for the most current Point Pelee population (2008-2012) rises sharply at < 50 individuals over multiple time scenarios, therefore, this was determined to be the Poor condition threshold (Parks Canada, 2015).

The condition of the skink population at Point Pelee National Park is well above the Good-Fair threshold (2013-2017: 197 ± 67.9 skinks) and has remained stable since the 2008-2012 monitoring period (80% CIs overlapping; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Average skink population size during each of the four 5-year monitoring periods. All periods show a total population census (i.e., all quadrats sampled), with the exception of 2013-2017, where 2015-2017 were population estimates (i.e., a subset of quadrats were sampled). Black error bars indicate the 80% confidence intervals. Dashed green line and red line show the “Good-Fair” threshold and “Fair-Poor” threshold, respectively.

Next Steps and Research/Monitoring Needs

The population of Common Five-lined Skinks at Point Pelee National Park has remained in good condition over the time period of 1998-2017 presented in Figure 3. Skinks at Point Pelee were experiencing a downward trend in the early 1990s attributed largely to disturbance and removal of woody debris by humans and illegal collection (Hecnar and Hecnar, 2013), however, the population saw improvement when the park began a project to increase the quality of habitat by adding more woody debris to stabilized dune areas in 1995. Woody debris provides essential shelter cover for this species.

Restoration of the LESSS habitat, which began in 2011, has also improved habitat for the population, especially in inland sites where natural succession had drastically reduced the amount of savannah habitat. Restoration efforts have converted dogwood thickets back to open savannah habitats through management actions such as cutting and prescribed fires. Skink monitoring has historically only taken place along park beaches, where the vast majority of the population was found. Future surveys will be expanded to newly restored interior LESSS sites in order to detect range shifts due to climate change or environmental stochasticity (e.g., large fluctuation in water levels).

More recently (2018-2019), monitoring has shown that the abundance of Common Five-lined Skink has declined at Point Pelee National Park and this is strongly correlated with high Lake Erie water levels. A similar trend has been found at Rondeau Provincial Park. Despite gains made in stabilizing skink populations through habitat and restoration projects, there remain serious concerns for this species’ continued persistence at these sites due to predicted negative impacts of climate change on shoreline habitats (i.e., decreases in protective winter ice is projected to increase vulnerability to coastal erosion (BaMasoud, 2013; BaMasoud and Byrne, 2011; 2012). Continued research, assessment, and conservation of Common Five-lined Skink are warranted to ensure protection of this endangered species.

References

- BaMasoud, A. (2013). Shoreline Changes in Point Pelee, Canada: An Airphoto-based Analysis. (Ph.D.), Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

- BaMasoud, A. and M. L. Byrne. 2011. Analysis of Shoreline Changes (1959-2004) in Point Pelee National Park, Canada. Journal of Coastal Research, 27(5), 839-846. doi:10.2112/jcoastres-d-10-00160.1.

- BaMasoud, A. and M. L. Byrne. 2012. The impact of low ice cover on shoreline recession: A case study from western Point Pelee, Canada. Geomorphology, 173, 141-148. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.06.004.

- Hecnar, S.J. and D.R. Hecnar. 2013. Five-lined skink research at Point Pelee National Park, 2012. Final Report. Leamington, Ontario, Canada.

- Parks Canada. 2015. Operational Review of the Ecological Integrity Monitoring Program of Pointe-Pelee National Park. Monitoring and Ecological Information Division. Natural Resource Conservation. Parks Canada Agency. Gatineau, Quebec, Canada.