Authors

Chris Mensing, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, chris_mensing@fws.govNicole LaFleur, Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, Nicole_lafleur@fws.gov

John Hartig, University of Windsor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, jhhartig@uwindsor.ca

Background

Bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) are large fish-eating raptors, averaging 10-14 lbs (4.5-6.4 kg) for females and 8-9 lbs (3.6-4.1 kg) for males, with an approximate seven foot (2.1 m) wingspan (Figure 1). The bald eagle has been selected as an indicator of aquatic ecosystem health by the Lake Erie Lakewide Management Plan and by the State of the Lakes Ecosystem Conference (SOLEC) (Environment Canada and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2003).

Figure 1. Mature Bald Eagle (Photo credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Bald eagles were documented in the early-1900s as being “evenly distributed” throughout Michigan (Michigan DNR 2005). The population then declined through the mid-1900s due to loss of nesting habitat and persecution by humans (shooting, poisoning, trapping, and electrocution). In the 1950s the decline of eagles in Michigan accelerated until they were on the brink of extinction in the 1970s. This trend was similar throughout the lower 48 states and southern Canada. This decrease was a result of several factors, most influential being the increased use of organochlorine compounds such as DDT and PCBs following World War II (Colborn 1991, Bowerman et al. 1995, Bowerman et al. 1998, Bowerman et al. 2003). Exposure to these contaminants in avian species causes reproductive failure, sterility, life-threatening deformities such as crossed bills and eggshell thinning, altered behavior such as impaired foraging abilities, increased susceptibility to disease through immune system dysfunction, and in cases of acute poisoning, death.

These reproductive impairments reached a peak in the mid-1970s, resulting in only 38% of Michigan’s bald eagle populations successfully fledging young. In 1980, bald eagles nesting along the Lake Erie shoreline experienced complete reproductive failure. Bald eagle recovery efforts in the U.S. and throughout North America were initiated in 1972 with the banning of DDT in the United States by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and in 1973 with the passage of the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). As a result, from 1981 through 2005 the Michigan bald eagle population has continually increased and continues to do so (Figure 2, Michigan DNR 2005).

Geographic Area of Coverage

For the purpose of this indicator report, the geographic area of coverage is southeast Michigan, including Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, St. Clair, Washtenaw, and Wayne counties. The results of long-term reproductive monitoring are summarized below for all bald eagles nesting within the seven-county region.Use as a biological indicator

Biological indicators are important tools for estimating ecosystem health. Bald eagles are ideal as biological indicators because they are a vulnerable species with low tolerance to environmental contaminants (Golden and Ratner 2003). The increasing population of bald eagles suggests that contaminants in the ecosystem are less prevalent. However, not all population shifts are due to environmental toxins. In Michigan, anthropogenic factors such as collisions with vehicles are the main cause of female eagle mortality and should be considered when planning for management action (Simon 2016).

Status and Trends

In Michigan, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and the USFWS coordinate a monitoring program aimed at assessing the health of bald eagles. For this indicator report, bald eagle data have been compiled from a combination of fixed-wing aircraft and helicopter surveys and citizen reports.

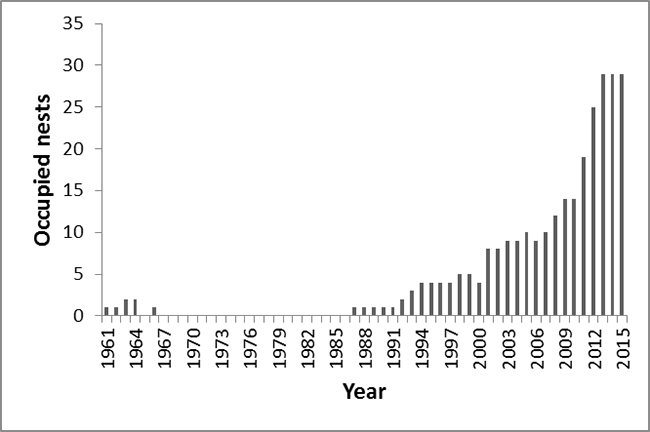

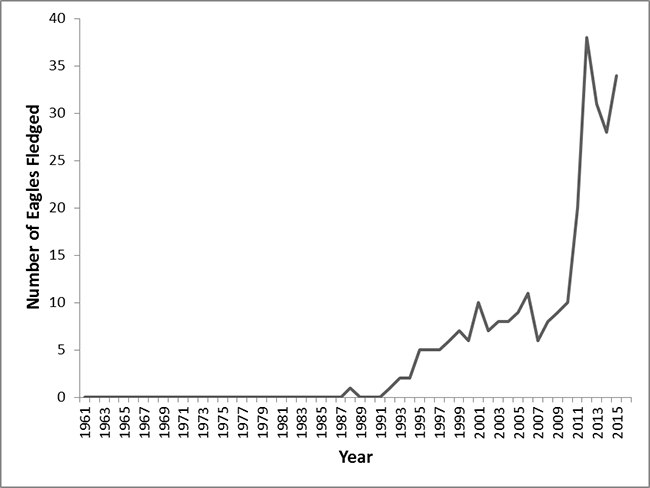

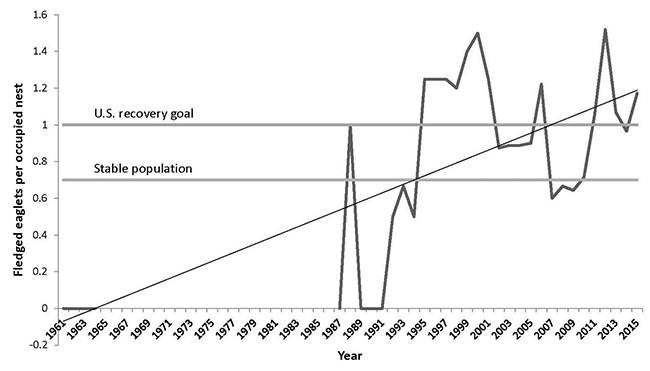

From 1961 to 1987 there were no bald eagles produced in Metropolitan Detroit due primarily to organochlorine contamination (Figure 2). Since 1991, there has been a steady increase in the number of occupied bald eagle nests per year in metropolitan Detroit. From 2012-2015, at least 25 active nests have been documented each year, resulting in the fledgling of 28 or more young per year. An average of 1.06 eaglets were fledged per occupied nest in southeast Michigan from 1995-2015, which is indicative of a stable or increasing population and meeting the U.S. recovery goal. In 2007, the USFWS removed the bald eagle from the endangered species list because their populations recovered sufficiently across the United States.

Figure 2A. Number of occupied bald eagle nests in southeast Michigan, 1961-2015 (data source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Figure 2B. Number of eaglets fledged in southeast Michigan, 1961-2015 (data source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Figure 2C. Number of eaglets fledged per occupied nest in southeast Michigan, 1961-2015 (data source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

Management Next Steps

The bald eagle remains federally protected in the U.S. under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, and is classified as a “species of special concern” in Ontario.

Efforts should be undertaken to protect existing nesting and foraging habitats (Watts 2015). Management should continue to place a priority on control of contaminants at the source and on the remediation of contaminated sediment “hot spots”, to ultimately ensure that contaminant levels in fish and other aquatic prey do not result in reproductive impairment of bald eagles. Reproductive outcomes and contaminant exposures should continue to be monitored. This species will also benefit from increased public outreach and awareness of the threats to the health of the species and the ecosystem.

Research/Monitoring Needs

Yearly monitoring of the bald eagle population should continue throughout the Detroit River and western Lake Erie watersheds. Eaglets should continue to be banded and have representative samples taken to monitor levels of contaminants, so as to determine health status of individual eagles and the ecosystems in which they reside. Contaminants of concern include organochlorine compounds and heavy metals, as well as emerging new generation compounds. Furthermore, additional laboratory and field studies may be necessary to further clarify the role of environmental endocrine disruptors on reproduction in avian populations (Bowerman et al. 2000).

References

- Best, D. A., Elliot, K. H., Bowerman, W. W., Shieldcastle, M., Postupalsky, S., Kubiak, T., J., Tillitt, D. E., and J. E. Elliot. 2010. Productivity, embryo and eggshell characteristics, and contaminants in bald eagles from the Great Lakes, USA, 1986 to 2000. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29(7): 1581 – 1592.

- Bowerman, W.W., J.P. Giesy, D.A. Best, and V.J. Kramer. 1995. A review of factors affecting productivity of bald eagles in the Great Lakes region: Implications for recovery. Environmental Health Perspectives 103 (Suppl. 4): 51-59.

- Bowerman, W.W., D.A. Best, T.G. Grubb, G.M. Zimmerman, and J.P. Giesy. 1998. Trends of contaminants and effects in bald eagles of the Great Lakes Basin. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 53: 197-212.

- Bowerman, W.W., D.A. Best, T.G. Grubb, J.G. Sikarskie, and J.P. Giesy. 2000. Assessment of Environmental Endocrine Disruptors in Bald Eagles of the Great Lakes. Chemosphere. 41: 1569-1574.

- Bowerman, W.W., A.S. Roe, M.J. Gilbertson, D.A. Best, J.G. Sikarskie, R.S. Mitchell, and C.L. Summer. 2003. Using bald eagles to indicate the health of the Great Lakes’ environment. Lakes & Reservoirs: Res. and Manage. 7: 183-187.

- Colborn, T. 1991. Epidemiology of Great Lakes Bald Eagles. J Toxicol. and Environ. Health. 33: 395-453.

- Golden, N. H., and B. A. Rattner. 2003. Ranking Terrestrial Vertebrate Species for Utility in Biomonitoring and Vulnerability to Environmental Contaminants. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 176: 67-136.

- Environment Canada and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2003. State of the Lakes 2003. Environment Canada and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, En40-11/35-2003E. pp. 103.

- Michigan Department of Natural Resources. 2005. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus).

- Simon, K. L., Bowerman, W. W., Rattner, B. A., Yonkos, L. T., Murrow, J. L., and C. R. Angel. 2016. Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) as Indicators of Great Lakes Ecosystem Health. Disseration submitted to the University of Maryland.

- Watts, B. D. 2015. Estimating the residual value of alternate bald eagle nests: Implications for nest protection standards. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 79(5): 776-784.

Links for more information

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service:

http://ecos.fws.gov/species_profile/servlet/gov.doi.species_profile.servlets.SpeciesProfile?spcode=B008 - American Bald Eagle Information:

http://www.baldeagleinfo.com/

Contact Information regarding Bald Eagle Reproductive Success

Chris Mensing

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, East Lansing Field OfficeE-mail Address: chris_mensing@fws.gov

Nicole LaFleur

Detroit River International Wildlife RefugeE-mail Address: Nicole_lafleur@fws.gov

John Hartig

University of Windsor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental ResearchE-mail: jhhartig@uwindsor.ca