Daniel Heath is heading GEN-FISH, a four-year project that involves creating a genomic toolkit to assess the health of freshwater species. Fish farm operators and consultants hired to do environment assessments are already lining up to be among the first to use the new technology.

Daniel Heath is heading GEN-FISH, a four-year project that involves creating a genomic toolkit to assess the health of freshwater species. Fish farm operators and consultants hired to do environment assessments are already lining up to be among the first to use the new technology.

Fish farm operators and environmental consultants are beating a path to the doors of Daniel Heath and his colleagues to be first in line to use a new genomic toolkit to assess the health of freshwater species.

Dr. Heath, a professor of integrated biology at UWindsor’s Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, is leading a $9.1 million national research project that involves, in part, developing a chip to determine whether fish are suffering from environmental problems like low oxygen levels, pollution or abnormal temperature.

The technique relies on gene expression, using minimally invasive blood samples or gill cells from fish and allowing the specimens to be sampled in the field then immediately released. It will replace traditional techniques that require fish to be caught and killed before testing — not ideal for species whose low populations put them at risk of extinction.

Heath said the technology will be ready to roll out to end users in the middle of next year at the earliest. But he’s already hearing from anxious fish farm operators and consultants who do environmental assessments for land developers. Testing for gene expression could prove to be cheaper and easier, they say.

“We had no idea people would be so interested,” said Heath, who joked he anticipated having to scrounge around for willing participants. “The level of buy-in is really high.”

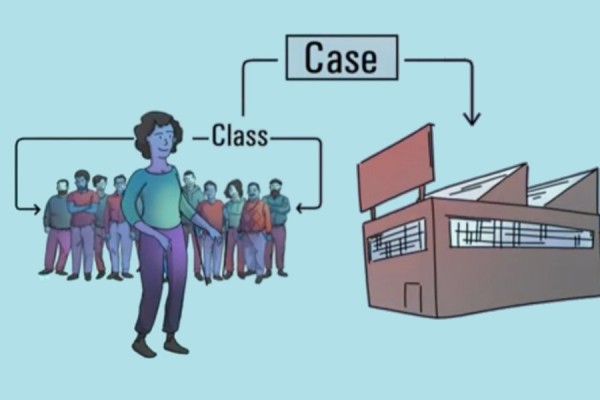

The four-year research project, named GEN-FISH, aims to develop a suite of procedures to identify species and monitor stressors based on gene expression. They will also develop web-based resources and software to help users monitor and react to threats.

At UWindsor, Heath is collaborating with fellow researchers Christina Semeniuk, Trevor Pitcher, Hugh MacIsaac, Oliver Love, Phil Karpowicz, Dennis Higgs, and Amy Fitzgerald. They are among more than 70 researchers from British Columbia to New Brunswick on the project that holds the promise of ensuring the sustainability of freshwater fish stocks in Canada for generations to come.

The project will also develop management tools based on a technique called environmental DNA, or eDNA. Heath is a pioneer in eDNA, which involves the collection and analysis of water to identify all the species that exist in the ecosystem from which the water sample was drawn.

The eDNA process relies on identifying genetic material in the water. It is less invasive and more comprehensive than traditional techniques that require specimens to be captured.

The process will be used to create what Heath calls a “fish survey toolkit” in the initial part of the project. The second part of the project involves creating the “fish health toolkit” which identifies gene expression markers to denote if the fish are healthy or stressed.

The toolkits GEN-FISH researchers are developing will make Canada a world leader in the complete and accurate assessment of freshwater fish populations. They will help scientists and managers overcome the logistics of surveying and monitoring Canada’s more than two million lakes and the rivers and streams that connect them.

“This is the largest application of genomic tools for freshwater fishery management and conservation in the world,” Heath said.

The project has received funding from the federal and provincial governments, with more in-kind contributions coming from other partners.

GEN-FISH has secured its funding with the help of Ontario Genomics, a provincial agency that works with federal funding agency Genome Canada to encourage genomics innovation. Ontario Genomics is also administering the project’s funding.

“This project is a perfect example of how genomics is foundational for the development of tools and technologies that provide solutions for our most pressing problems,” said Bettina Hamelin, president and CEO of Ontario Genomics.

“At Ontario Genomics, we envision a world of healthy people, a healthy economy, and a healthy planet through genomics innovations. The GEN-FISH team’s work aligns with our goals to protect our natural habitats that constitute the livelihoods of rural, northern and Indigenous communities.”

GEN-FISH began in earnest in January, but the pandemic forced researchers to rethink their approach.

“Many of our government partners shut down or scaled back on field work,” Heath said.

Researchers were able to get back into the field by late summer, but in the interim, they relied on previously collected data, compiling eDNA profiles of fish communities, he said.

“We’ve actually made significant steps forward. We’re making progress despite the restrictions of COVID.”

—Sarah Sacheli